The lines within the film’s indoor environments tend to place the characters into narrow rectangular frames that suffocate the characters. Sliding glass doors keep David Staebler (Jack Nicholson) separate from the events that are unfolding in the adjacent room, but still allow him to glimpse a white character being pushed off-screen by a well-attired black man. The wall that briefly hides the scene, and the placement of the camera, places the audience with David, restricting our view and emphasising the criminal and mysterious atmosphere associated with Lewis’ (Scatman Crothers) cinematic mob world. The white man immediately reappears in sight, trapped by the geometrical skeleton of the glass walls (fig.1); the square panels here reference the preceding scene in jail from where Jason (Bruce Dern) had asked for David’s help.

The mafia boss characteristics embodied by Lewis’ character strikingly emerge from the moment he steps into the room and towards the white man. By doing so he confines him to the very right side of the frame and makes him struggle to remain within the shot, evidencing the power imbalance (fig. 2). The line dividing the two rooms represents the power contrast between two social groups, the lower working class and a powerful criminal class. Lewis is the only character able to navigate, or cross, the line. Similarly, Lewis appears to have the power to keep Jason in or out of prison (Webb 2015).

The squared glass panels of the white walls work not only as a visual cage (fig.1 and fig. 2); they also provide a symbolic cross section of Lewis’ gangster world, making it possible to associate such squares with the Monopoly board game, which Le Fanu points out as being the lens through which Kovács’ photography captures the stark geometry and transactional nature of Atlantic city. Lewis is the King of Marvin Gardens because he is the only character who survives the inexorable degradation of the crumbling districts the film traverses. This may cause moral discomfort to the audience as his power is achieved against a backdrop of the corrupt and immoral means by which he is presumed to have obtained his wealth. As David obediently waits for Lewis in this meeting (because he was told to do so), Lewis is portrayed as being the embodiment of the success to which Jason aspires, even though this is the result of criminal misdeeds.

The costumes worn by the characters also delineate their social standing and psychology. The red sweater worn by Lewis in combination with his mafia boss pinkie ring, golden watch and ostentatious scarf reflects his desire to show off his hard-earned (albeit illegally obtained) wealth and makes him stand out against the neutral colour palette chosen for the setting and the other characters’ clothes. The plaid hat works as a crown, its checked pattern symbolising his holding of a monopoly over Atlantic City. The black Queen of Spades playing card in his hand, alongside the recurring motif of alcohol bottles whenever Lewis is in shot, further reinforces the combination of power, prestige and criminality (fig.2).

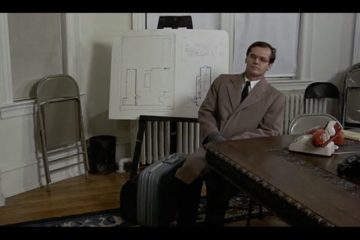

As David is sitting waiting to be received by Lewis in the sequence, his image is, in contrast, “satirised as bland and sterile” (Benshoff & Griffith, 53). The neurotic traits intrinsic to David’s character are emphasised by his appearance: the glasses, gloves and receding hairline as well by his rigid posture. The use of a high-angle wide shot places him in the middle of a chaotic room, making the audience perceive him as somehow lost and defenceless. The vertical lines of the window and radiator, converging centrally with the suitcase and table, trap David in a constrictive frame that limits his movements (fig.3). These choices visually signal David’s inability to make decisions of his own and indicate his social submission to Lewis. Ultimately, David does, in leaving the room, demonstrate limited agency. Yet, he does so because of his failure to address Lewis and ask for clarification. As a result he is portrayed as nothing more than a Monopoly pawn in Lewis’ game. After all, “Jason says, Lewis knows”.

The red and white chair on which David is sitting as well as red and white inverted phone receivers that he cannot prevent himself from swapping around are symbolic colours. They frequently recur in the Atlantic City shop signs, possibly mimicking the Monopoly game logo and therefore further reinforcing the game-like quality that depicts Lewis as king and player. This further emphasises David’s powerlessness over a world that he tries to rationalise (by rearranging the receivers) but over which he ultimately does not have any control.

Another interpretation of the use of colour here might have it that the colour red enters the film in the opening scene as David tells his fictional anecdote about his and Jason’s inaction during his grandfather’s death when they were children. As he tells the story, the red flashing “on the air” light illuminates his face. Later on, the colour acquires further relevancy in the connotation of Jason’s character whose figure is often juxtaposed to the majestic red curtains of the hotel and whose coat lining is also of a vivid red. In contrast, David wears anonymous black or white clothes, whose dullness blends him into the surrounding environment and adds to the perception of him as a bland and almost marginal character. This is further remarked by Jason: “you look like a priest!”. The use of red ceases in the film from the moment Jason’s blood stains the white bathroom door.

Ultimately, in the sequence, Lewis, with the foreshadowing quality of a god, pronounces an emblematic sentence: “If you want to change the seat though, go right ahead”. Ignoring Lewis’ suggestion, a disoriented David remains on the chair in which red and white coexist, as they eventually will on the bathroom door. Then he swaps the phone receivers in anticipation of the separation of him and his brother. Lewis’ deification is the ultimate product of Jason’s chasing of the American dream. In fact, Jason aspires to become the King of Marvin Gardens by relying on the same illegal means by which Lewis established his power and well being. This exemplifies the notion of the hopeless aspirational American citizen who sees in criminality a shortcut to economic empowerment.

References

Benshoff, Harry, and Griffin, Sean. America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender and Sexuality at the Movies. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Print.

Le Fenu, Mark. ‘The King of Marvin Gardens: A Killing’. Criterion.com. Web. 18 Mar 2018.

Webb, Lawrence. New Hollywood in the Rust Belt: Urban Decline and Downtown Renaissance in The King of Marvin Gardens and Rocky’. Cinema Journal. 54.4 (2015): 100-125. Pri

ind

Adriana Saetta is a BA Hons Film Studies student at Queen Mary. She is from Milan, Italy and aspires to become a film director. She enjoys exploring London with her camera, looking for new ideas and opportunities.

Please obtain permission before redistributing. Copyright © 2018 Adriana Saetta